Recently, season 3 of Alice in Borderland was released on Netflix. While browsing the endless content about the show online, I stumbled upon an image that instantly took me back to my university days studying Information Security, reminding me of concepts like Bloom Filter and the Birthday Paradox.

Can you believe it? With just 23 people in a room, the probability that at least two share a birthday exceeds 50%. And with 78 people, that number jumps to a staggering 99.9%! This isn't magic; it's a famous mathematical phenomenon known as the Birthday Paradox.

Why is it called a Paradox?#

First, we need to understand why it's considered a paradox. With 365 days in a year, our intuition tells us it should take about 182 people (half of 365) to reach a 50% probability.

However, the reality is that it only takes 23 - a number that feels incredibly small compared to 182. This vast gap between intuition and mathematical reality is what makes it so "paradoxical".

Cracking the Paradox: The Mathematical Solution#

The key to solving this paradox is to calculate the complementary probability. Instead of calculating the probability of a match directly, we calculate the probability of no matches and subtract it from 1.

Step 1: Simplifying Assumptions

Let's assume a year has 365 days and that birthdays are uniformly distributed (ignoring leap years, seasonal variations, etc.).Step 2: Calculate the Probability of NO Shared Birthdays

Person 1: Can choose any birthday. Probability of no collision: 365/365.

Person 2: Must choose a different day. Probability: 364/365.

Person 3: Must differ from the first two. Probability: 363/365.

...

Person n: Probability: (365 - (*n* - 1)) / 365.

Therefore, the probability that all n people have different birthdays is:

\(P(\text{no match})=\frac{365}{365}\times \frac{364}{365}\times \frac{363}{365}\times…\times\frac{(365 - (n - 1))}{365}\)

Step 3: Calculate the Probability of AT LEAST ONE Shared Birthday

Simply subtract the above result from 1:

$$P(\text{at least one match}) = 1-P(\text{no match})$$

This can also be written as:

$$P(n) = 1-\frac{365!}{(365-n)! \times 365^{n}}$$

Putting the Numbers to the Test#

Let's apply the formula to the numbers from the original image:

With n = 23 people:

P(23) = 1 − (365/365 × 364/365 × ... × 343/365) ≈ 0.5073 or 50.73%With n = 78 people:

P(78) ≈ 0.99926 or 99.93%With n = 183 people:

P(183) ≈ 0.9999999999 (virtually 100%)With n = 365 people (and The Dirichlet Pigeonhole Principle):

With 365 people, a shared birthday isn't technically guaranteed (theoretically, they could all have different birthdays if incredibly lucky), but the probability of a match is extremely high. Only when you have 366 people (more than the number of days in a year) does the Dirichlet Pigeonhole Principle guarantee that at least one pair shares a birthday.

Finding a General Formula#

In the real world, calculating large factorials is difficult. Therefore, we typically use the following approximation:

Let:

N: number of possible values (e.g., 365 days).

k: number of objects (e.g., number of people).

The probability of at least one collision is approximately:

$$P(collision)\approx1-e^{-\frac{k^{2}}{2N}}$$

For those curious about the derivation, it's not as hard as you might think!

Starting from the formula above:

$$P(\text{no match})=\frac{N}{N}\times \frac{N-1}{N}\times \frac{N-2}{N}\times…\times\frac{(N- (k - 1))}{N} = \prod_{i=0}^{k-1}(1-\frac{i}{N})$$

Taking the natural logarithm:

$$\ln P(\text{no match}) = \sum_{i=0}^{k-1}\ln(1-\frac{i}{N})$$

According to the Taylor series approximation, for very small \(x\approx0\):

$$\ln (1-x) \approx -x$$

Since k << N, we can use the approximation \(\frac{i}{N}\approx0\). This leads to:

$$\ln P(\text{no match})\approx \sum_{i=0}^{k-1}(-\frac{i}{N}) =-\frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=0}^{k-1}i = -\frac{1}{N}\cdot \frac{k(k-1)}{2}$$

Therefore:

$$P(\text{no match})\approx e^{-\frac{k(k-1)}{2N}}\approx e^{-\frac{k^{2}}{2N}}$$

And finally:

$$P(\text{at least one match})\approx 1-e^{-\frac{k^{2}}{2N}}$$

Beyond Birthdays: A Pillar of Cybersecurity#

The Birthday Paradox isn't just for party tricks. It's a fundamental concept in cybersecurity.

Let's take a universally relatable example: logging into an account.

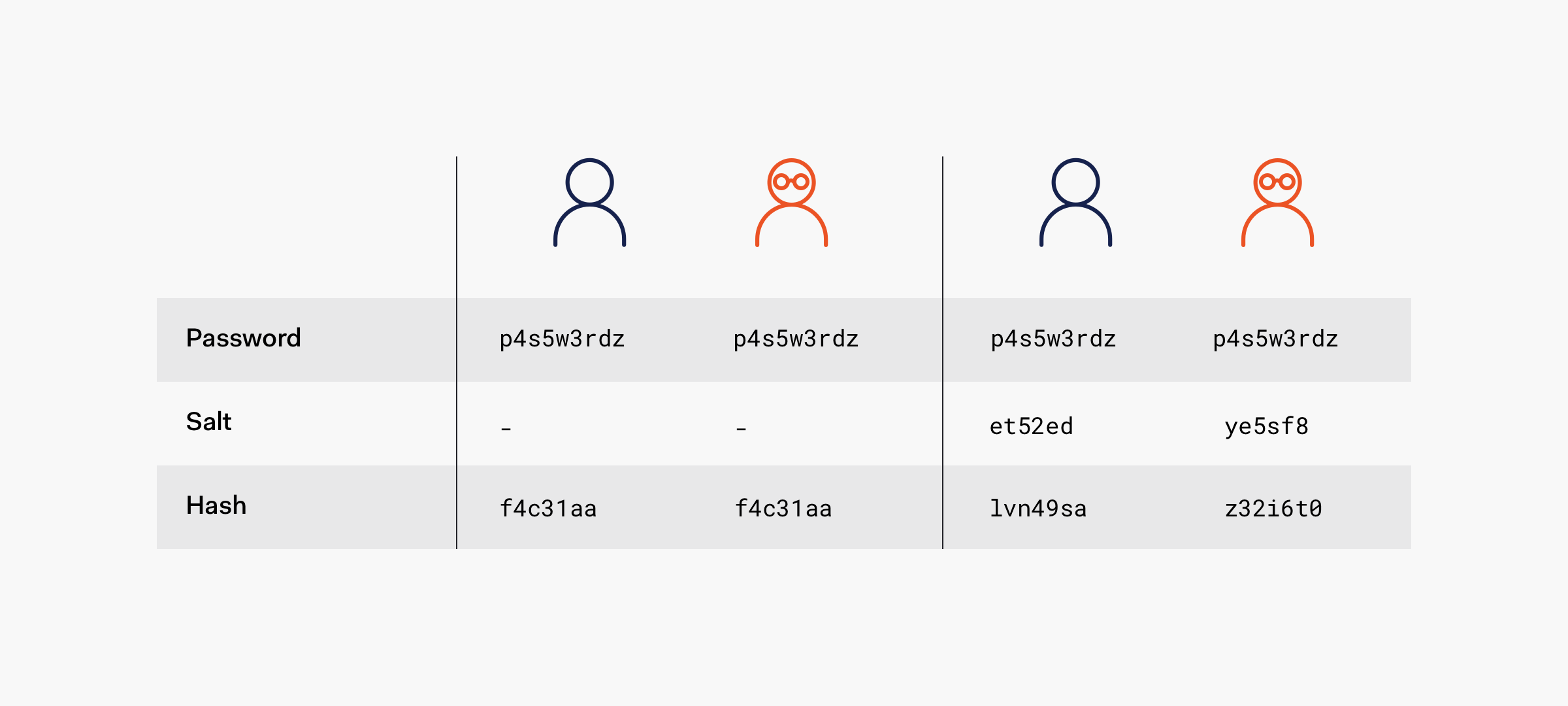

Typically, a system never stores your original password in its database. Instead, it stores a cryptographically hashed version. The simple reason is that if anyone (be it a developer or a hacker) gains access to the database, they cannot read the actual passwords.

However, hashing alone is not sufficient. If a hacker knows a common password like "123456", they can find all other accounts using the same hash. Worse, if they have a pre-computed rainbow table, they can reverse the hashes for common passwords in an instant.

This is why we add "salt" to each password before hashing. Each user gets a unique, random salt. This ensures that even if two users have the same password, their hashed results are completely different. In other words, salt prevents hackers from using a "one-size-fits-all" attack.

But how big does this salt need to be to make the probability of two salts colliding nearly zero?

Let's return to our Birthday Paradox. Suppose your system has 1 billion users (k = 10⁹). We can use our formula to see how different salt sizes hold up: \(P(\text{collision})\approx 1-e^{-\frac{k^{2}}{2N}}\)

| Salt (bytes) | Bits | N=2bits | P(collision) |

| 1 | 8 | 28 | ≈ 1 (certain) |

| 2 | 16 | 216 | ≈ 1 (certain) |

| 3 | 24 | 224 | ≈ 1 (certain) |

| 4 | 32 | 232 | ≈ 1 (certain) |

| 5 | 40 | 240 | ≈ 1 (certain) |

| 6 | 48 | 248 | ≈ 1 (certain) |

| 7 | 56 | 256 | 0.999031 (≈99.90%) |

| 8 | 64 | 264 | 0.026741 (≈2.67%) |

| 9 | 72 | 272 | 0.000105874 (≈1.06×10⁻⁴) |

| 10 | 80 | 280 | 4.136×10⁻⁷ |

| 11 | 88 | 288 | 1.616×10⁻⁹ |

| 12 | 96 | 296 | 6.311×10⁻¹² |

| 13 | 104 | 2104 | 2.465×10⁻¹⁴ |

| 14 | 112 | 2112 | 9.630×10⁻¹⁷ |

| 15 | 120 | 2120 | 3.762×10⁻¹⁹ |

| 16 | 128 | 2128 | 1.469×10⁻²¹ |

As we can see, with a salt ≥ 12 bytes (96 bits), the probability of a collision becomes extremely small (10⁻¹² and below), making it practically impossible in a real-world scenario. However, in security research and implementation, we must also consider execution factors and other attack vectors for a holistic security assessment - topics that extend beyond the scope of this article.

Conclusion#

The Birthday Paradox is a perfect demonstration of how human intuition can be easily misled by numbers. It teaches us a crucial lesson: in a complex and interconnected world, things that seem incredibly rare can actually have a surprisingly high probability of occurring.

Next time you're at an event with more than 23 people, challenge yourself to find someone who shares your birthday. You might not only be surprised by the result but also have a fascinating story about mathematics to share with everyone.